by Eric Meier

“What’s the best type of wood finish to use for this wood?” I’m always amused when I get asked this question, as if there is only one single “right” finish to use for a given wood species. The real answer would be, “it depends…” It all depends on what type of look you’re going for, what level of protection you want, how much maintenance you’re willing to do, etc.

But the more I think about this question, the more I realize that although there is no “wrong” finish for a given wood species, there are definitely some finishes that seem to work better in certain situations than others. It all depends on context. With this in mind, the following is an overview of a number of consumer-level wood finishes, as well as my honest assessment as to which ones work best, and when.

Rub-in oils

The Lowdown: These are more or less pure oils, and they are extremely simple to apply: you just rub them in, wait a few minutes (or hours) to allow the oil to penetrate the wood, and then wipe off the excess. The two main players in this category are tung oil and linseed oil. Given enough time, both will naturally dry or cure on their own. (As opposed to other natural oils—think canola or olive oil—which just stay “wet” for an indefinite period of time and would eventually go rancid.)

Quartersawn White Oak box finished with boiled linseed oil

Boiled linseed oil (BLO) tends to be the cheaper of these two oils, and since raw linseed oil can take a very long time to dry, heavy-metal driers (cobalt/manganese salts) are added to accelerate the curing process in lieu of actually “boiling” the oil. For something closer to a true boiled linseed oil without the added chemicals, try something like Tried & True Original Wood Finish, which is FDA approved for direct food contact in both its cured and uncured state.

Tung oil is very similar, except that raw tung oil still eventually dries and can be used as-is. (Look for words such as “raw,” “pure,” or “100%” in the name to find the straight oil.) There are also heated/altered versions of tung oil which, like linseed oil, helps the oil polymerize (fancy chemistry word for “dry”) faster. Many “tung oil” finishes sold on the market today are not truly pure tung oil, but may incorporate a portion of tung oil with other resins and could really be considered an oil-varnish blend, discussed further down.

Where it works: These oils give a rich warmth to the wood surface, and linseed oil in particular tends to accelerate and exaggerate the natural patina of the wood. They tend to impart a satiny sheen that isn’t too glossy, replicating a “natural” wood look. However, because it’s in the wood rather than on it, these oils don’t offer the best protection and wear/moisture resistance, and should be used on places that receive minimal wear, or on pieces where fresh coats of oil can easily be reapplied.

Best Bets: Walnut, mahogany, oak, cherry (if you’re looking for a darker, richer natural patina with low sheen).

Fails: Anywhere a glossy, high-sheen finish is desired, or any place where wear/durability will be an issue. Also, linseed oil isn’t the best for woods like padauk, purpleheart, or cocobolo (if you like the color of the wood as-is, this isn’t the finish to use; light-colored woods will yellow, and colorful woods age/darken much faster).

Oil-varnish blends

The Lowdown: Oil-varnish blends are an extremely popular wood finish. They combine the ease-of-application of rub-in oils, but are fortified with resins to give them a bit more durability. Various other additives may be found as well, such as dyes/pigments, driers, or UV inhibitors. Depending on the composition of the blend, it may be more able to build up a moderate sheen (semi-gloss) on the wood surface.

One of the biggest drawbacks to these sorts of finishes is that they are somewhat of a mystery in terms of their composition. In nearly all cases, they will use a linseed or tung oil base, but beyond that, there’s no telling what exactly is in each product. Many times, a host of products are cleverly named as a marketing ploy to increase sales (e.g., “teak oil” for Teak furniture, “antique oil” for antique furniture, etc.) At times, an oil product may be nothing more than a drastically thinned-down version of a pure rub-in oil with added driers to make it easier to recoat in less time.

Where it works: In most instances, oil-varnish blends work in much the same way and in much the same capacity as rub-in oils. They soak into the wood and provide a thin, natural-looking finish that’s easy to apply. They may have a bit more versatility in terms of sheen and color options. Durability of the finish is slightly better than pure oils (due to added resins), but is usually still inadequate for high-traffic, high-wear pieces.

Best Bets: [Same as rub-in oils] walnut, mahogany, oak, cherry (if you’re looking for a darker, richer natural patina with low to mid sheen).

Fails: [same as rub-in oils] Anywhere a glossy, high-sheen finished is desired, or any place where wear/durability will be an issue. Also, linseed oil-based finishes aren’t the best for woods like padauk, purpleheart, or cocobolo (if you like the color of the wood as-is, this isn’t the finish to use; light-colored woods will yellow, and colorful woods age/darken much faster).

Varnishes

The Lowdown: Varnishes are known for their durability and toughness. A variety of sheens are available: from satin to glossy. They are generally oil-based, and contain synthetic resins such as phenolic, alkyd, and urethane.

The most desirable attribute of varnishes is that they are able to build up multiple coats (known as “film-building”), which enable them to excel at truly protecting the wood. When slopped on with a brush in several thick coats, they’re notorious for creating a plastic-like appearance on wood surfaces. Thinned-down formulations also exist, which can be wiped on, but still require slightly more care to apply than a strictly rub-in oil finish.

What sets varnishes apart from one another is their formulation and quantity of resins. Finishes that contain a higher percentage of oils and less resins are called long-oil varnishes, and tend to be more elastic and soft—perfect for outdoor applications and areas that receive a lot of moisture (Epifanes is a good example of a long-oil varnish). Toward the other end of the spectrum are medium and short-oil varnishes, which contain a higher concentration of resins and cure to a harder finish—good for table tops and floors (such as Behlen’s Rockhard Table Top Varnish).

Where it works: Anywhere toughness is paramount, varnishes should be your go-to option. Also, the glossy properties of varnish, when applied well, can give an eye-catching sophistication to a piece.

Best Bets: Exterior wood surfaces (boats, decks, outdoor furniture), as well as high wear areas (flooring, tabletops, and cabinets). Teak, white oak, cherry (use water-based varnishes such as Minwax’s Polycrylic to preserve lighter colored woods such as maple).

Fails: Oily tropical hardwoods (can have issues curing properly), as well as any project where a natural or rustic look is desired. Wormy chestnut, ambrosia maple, banksia pods.

Evaporative finishes

The Lowdown: The two primary types of evaporative finishes seen today are shellac and lacquer; they’re a bit different than varnishes or oils as they are composed of a solvent and a resin, and simply rely on the solvent to evaporate, leaving the resin behind. Shellac uses a denatured alcohol (DNA) solvent with a natural resin—secreted by lac bugs found in India and Thailand. Lacquer uses a special blend of solvents referred to simply as lacquer thinner, with alkyd and nitrocellulose resins. Because they rely on evaporation (rather than oxidation), they both tend to be very fast-drying. Like varnishes, they are film-building and sit on top (not in) the wood, and are available in a number of different sheens. They offer better protection than oil or oil-varnish blends, but fall short of the supreme toughness of varnishes.

One of shellac’s claims to fame is its compatibility with a variety of surfaces and topcoats. The old adage is: shellac sticks to everything, and everything sticks to shellac. Traditionally, shellac is mixed from shellac flakes dissolved in alcohol, but premixed commercial varieties are also available. The downside to this is that shellac has a somewhat short shelf-life (about one year from the time it’s mixed). Instructions on mixing your own shellac are given in my page on finishing exotic woods. Zinsser’s SealCoat is an excellent shellac product that is premixed and relatively shelf-stable.

Bonus note on shellac: Based on an experiment of wood finishes for African padauk put on by Woodworker’s Source, it was found that shellac outperformed all other major finish types in preserving the orange color of the padauk. My theory as to why this is the case is that padauk’s colors (as well as many other exotics) are very much soluble in alcohol, and the solvent present in the shellac may actually be pulling some of the wood’s natural colors out of the wood surface and locking them into the lac resin.

Lacquer tends to be a little tougher and more resilient than shellac. Many professional furniture makers have dedicated spray booths and spray lacquer onto their pieces with great efficiency. But even without expensive spray equipment, much of the benefits of lacquer can still be reaped in the form of brushing lacquer, as well as spray-cans of lacquer sold at hardware stores. Besides the somewhat noxious solvents contained in lacquer, the only other downside is that the nitrocellulose resin (contained in ordinary lacquer) tends to yellow with age, which may be an issue on lighter-colored woods. A special type of lacquer—cellulose acetate butyrate (or CAB)—made with different, non-yellowing resins is also available.

Where it works: Great for interior projects that will see a moderate amount of use (again, varnishes should be used for the most demanding applications). Choose an evaporative finish if you have a very colorful or ornately figured project that you want to highlight in all its glossy glory. Some of the most dazzling and renowned wood finishes in the world have historically been from padding very thin coats of shellac onto the surface of the wood (a technique called french polishing) until an immaculately clear shine emerges.

Best Bets: Rosewoods, colorful exotics (padauk, purpleheart, bloodwood, cocobolo), and burls.

Fails: Evaporative finishes tend to have poor heat and chemical resistance (its own solvent is capable of re-dissolving the cured finish), and should be restricted to interior projects. Shellac really only comes as a glossy finish, and must be rubbed out by hand to a lower sheen (using #0000 steel wool

) if a satiny finish is desired.

Fill, Level, and Buff for the Win!

The Lowdown: With all film building finishes (polyurethane, tabletop varnish, shellac, and lacquer), there’s just a few critical elements missing from achieving a flawless, glass-like surface. The first is the pores of the wood. Some woods have small enough pores that it doesn’t matter (maple, cherry, beech, boxwood, holly, and poplar), which are sometimes referred to as close-grained woods. But many other woods have larger pores that the finish will sink into, creating unevenness in the finish film, and ruining the smooth-as-glass effect. These open-pored or open-grained woods include a bunch of common favorites, as well as many exotics, such as: oak, walnut, mahogany, ash, sapele, purpleheart, zebrawood, bubinga, teak, cocobolo, and so forth.

The foundation to every mirror-like gloss finish is an underlying smooth wood surface. It is absolutely critical with open-grained woods that the pores be filled in order to obtain a smooth wood surface before any finish is even applied to the wood. For natural colored woods (in varying shades of brown), an oil-based pore filler can be used. (I greatly prefer oil-based fillers over water-based products because they have less of a tendency to shrink back into the pores over time, material won’t come out of the pores during sanding, and they generally fill the pores in a single application.) These fillers can also be stained to roughly match the color of the wood being filled. With multi-colored woods (such as zebrawood) or colorful woods (like padauk), a transparent grain filler should be used. I prefer spreading a thin layer of thick CA glue over the wood surface with an old credit card or playing card (using a fan for ventilation), spraying accelerator, and then sanding the surface flat with 200 – 300 grit sandpaper.

Besides the pores, the second obstacle standing in the way of achieving a glassy wood surface is minor imperfections. No matter how perfectly a finish is brushed, sprayed, or wiped on, there will always be imperfections in the final topcoat. These make a bigger difference than you may realize. Dust, drips, unevenness, brush hair, lint, haze, and a host of other imperfections mar the work of even the most assiduous of laborers. The finish will need to be leveled with fine-grit sandpaper, and then buffed up to the desired sheen. Leveling should be done carefully with 200 – 600 grit sandpaper. Because of the risk of sanding through to raw wood, most finishers that intend to level a finish will intentionally build up a thicker film to have a greater margin of error. For spray lacquer, the norm seems to be about 10 coats—brushed finishes should generally require slightly less than that.

Once the finish has been adequately leveled (the wood surface should be uniformly dull—any glossy/low spots remaining indicate incomplete leveling), you can be assured that every possible imperfection and irregularity has been removed from the finish film. The finish is flat and flawless—with no luster whatsoever. All that’s left is to restore the gloss using very fine sandpaper and buffing compounds. After using normal sandpaper up to about 800 grit, I’ve found that 1000 grit Abralon discs are absolutely fantastic at preparing the finish for the buffing wheel. After the Abralon, I use a cotton buffing wheel with some Menzerna buffing compound applied to the wheels to bring the finish up to a candy-like shine.

Where it works: Fine woodworking. Anywhere that you’d like to show off the details of your wood projects with a new-car-paint level of shine.

Best Bets: Just about anything with an interesting grain or color. walnut, oak, mahogany, cocobolo, rosewoods, snakewood, and so forth.

Fails: Outdoor projects (mother nature will laugh at all your efforts and subsequently trash your hard work in short order). Carved or irregular objects can be very tricky if not impossible to level or buff out. Very light or unfigured woods (plain maple, birch, or pine) aren’t flattered much by this technique.

Specialty Finishes

The Lowdown: In certain circumstances, you may want/need to use a specialty wood finish that doesn’t quite fit the characteristics of any of the above categories.

One product that is very similar to the pure oils such as tung or linseed is mineral oil. Mineral oil doesn’t cure (polymerize), nor does it go rancid. It just sort of “is.” And for a butcher block or other food utensil, that’s okay. The idea is that this harmless, innocuous substance penetrates the wood and remains there, helping to drive out moisture and preventing bacteria from getting lodged within the wood and breeding. Mineral oil just stays somewhat “wet” and needs to be recharged and replenished from time to time.

Although an adhesive, CA glue can also be used as an actual finish for small turned items. Thick CA glue is applied to the piece via a paper towel with the lathe on a slow speed. The glue is then allowed to dry (or sprayed with an activator) and then sanded with very fine grit sandpaper. This process is repeated until a sufficiently thick finish has been formed, and then it is leveled and buffed in much the same way as any other film finish. The resulting finish is very hard, strong, and long-lasting.

Finally, there is paste wax. In most cases, wax should be seen as a temporary finish. It’s generally used in new projects to add an extra layer of protection to the wood after the final finish has been applied and buffed. In older projects and restorations, it’s used to bring back some of the shine of a piece’s younger days, and to help mask and scratches or imperfections in the wood. But with all of waxes’ cosmetic improvements to a wood surface, it should be remembered that wax will eventually rub off with wear. (Also keep in mind that despite any marketing pitches, wood does not “need” wax. Wood is not “thirsty.” Wood reaches an equilibrium moisture content with the surrounding air based on the relative humidity of the environment.)

See also:

Are you an aspiring wood nerd?

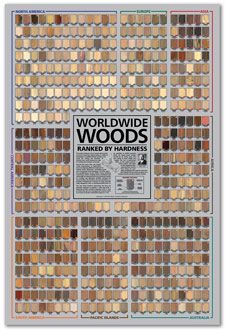

The poster, Worldwide Woods, Ranked by Hardness, should be required reading for anyone enrolled in the school of wood nerdery. I have amassed over 500 wood species on a single poster, arranged into eight major geographic regions, with each wood sorted and ranked according to its Janka hardness. Each wood has been meticulously documented and photographed, listed with its Janka hardness value (in lbf) and geographic and global hardness rankings. Consider this: the venerable red oak (Quercus rubra) sits at only #33 in North America and #278 worldwide for hardness! Aspiring wood nerds be advised: your syllabus may be calling for Worldwide Woods as part of your next assignment!

The poster, Worldwide Woods, Ranked by Hardness, should be required reading for anyone enrolled in the school of wood nerdery. I have amassed over 500 wood species on a single poster, arranged into eight major geographic regions, with each wood sorted and ranked according to its Janka hardness. Each wood has been meticulously documented and photographed, listed with its Janka hardness value (in lbf) and geographic and global hardness rankings. Consider this: the venerable red oak (Quercus rubra) sits at only #33 in North America and #278 worldwide for hardness! Aspiring wood nerds be advised: your syllabus may be calling for Worldwide Woods as part of your next assignment!

I have a question: Making a dining table using knotty alder – has a lovely grain. Can you use Maloof oil as the primary coat, then a sealer (such as shellac) followed by a varnish? Will it appropriately darken the wood and keep the nice grain? Can anyone help here with this question? thanks.

I’m glad you talked about how shellac is good for interior projects that experience moderate use. We are thinking of getting my old rocking chair refinished to preserve the wood’s integrity, so I’m trying to figure out what to go with. I love the look of shellac, but the chair doesn’t ever get used, so we might try something else first. Maybe a wood finishing company could help me select the right thing after seeing the chair.

Hi Erik, Great article on wood finishes. I recently glued up wood samples of domestic and exotic woods and then tried to put a finish on them. The first time I used Shellac for oily woods and then applied my Winwax polyurethane finish. The final out come wasn’t very durable, I could scrap the finish off with my finger nail feeling almost like a waxy substance. I removed everything and started over. This time I just used the polyurethane and had the same out come scrapping the finish off with my finger nail. The end products will be used in… Read more »

You might want to test your finish products on a scrap piece of wood first to see if they’ve one bad or are in some way defective (possibly due to improper storage). If your poly could even by scraped off of domestic woods like walnut, then something is definitely wrong. Also, keep in mind that shellac should be fresh and dewaxed — it should dry to a hard, brittle film. And I’ve found you need at least two coats of shellac for some woods (preferably three) in order to effectively block the anti-oxidants in the wood from interfering with the… Read more »

Thanks Erik, The Shellac was the “dewaxed” type and was just bought new that week. I did use several coats with light sanding between them for the Shellac. I’m baffled whey the polyurethane didn’t adhere to the bare walnut and the oaks. Could a person sand the surface too smooth so the finish can’t be absorbed?

I’d get another can of poly. That sounds like the culprit.

I bought Ephifanes Clear Varnish. Great product. Question on finishing butternut. The unfinished sample on your web-site looks like the gray tone I’d like. The finished sample looks…tan. To keep the color from changing, I could use General Finishes Clear Poly…but I don’t like the look of the finished piece. Can you recommend a finish for butternut that would keep it as close to natural as possible, and give it a high gloss like Ephifanes produces? Thanks.

Hi Eric!

Awesome article! I have just had a fresh new mahogany front door installed and was wondering if you had any suggestions on how to attain the fresh looking finish that linseed oil or mineral oil gives but also the durability needed for a front door. I am interested in the oil varnish blends but am worried they might be too glossy?

Thanks for any help you can give!

Thanks for this article! I have a bit of a long, drawn out question… I am taking on a project using birch plywood. It will be a layered topographical map, something like the one in the picture. My plan is to stain each of the “earth” layers – progressively darker at the higher elevations, and to color each of the “water” layers. For the water, I want to achieve a sort of “wash” effect, something like the second picture, where you can still see the grain of the wood. Since I can’t find blue stain, my hope is to use… Read more »

I would use a wood dye rather than a paint or stain for the blue. Transtint would be an excellent choice for this, though a bit spendy. You would then be free to topcoat with whatever you wish. There’s technically no such thing as “teak oil” per se, it is more of a marketing term, and it can have any number of different types of oils (such as linseed or tung oil) in the recipe.

Please help! I have no idea what kind of wood this is, despite a ton of research..I want to finish it with something dead simple, as I don’t want to move it from it’s spot, and I’ve never finished anything..I was thinking tung, or just a wax over the current raw wood, and I’m good with it darkening..Thoughts? It’s a desk, btw..

From the best I can tell… I would bet highly your desk top is hickory.. If your a novice Practice brushing minwax polycrylic .. it’s brushable and water borne… Thin it down 10% by volume with distilled water or if you can find it 5% propylene glycol. and it will brush and level well for you… samples first!

I have recently aquired a sample a wood named Golden Phoebe, it has a very high lustre and a golden yellow colour, it doesn’t seem to work well with my shellac. Anyone got any suggestions as to what finish to use?

You failed to mention melamine, which gives a much more durable finish than polyurethane and does not yellow the wood as much.

Also there is a process of using ethylene glycol that essentially fills the entire woods pores with a waxy polymer. This seems to be the most protective wood treatment other than creosote (except that it does not affect the appearance).

Thanks for the advice and Q&A on this page, Eric. I have turned a shallow bowl/platter in what I believe to be a red gum/eucalyptus and I’ve filled several gaps with an epoxy resin which I tinted (see image). Normally I use Danish oil to finish my wood because I prefer the semi-matt finish to gloss. Will Danish or lemon oil go over epoxy resin without problems or will I have to carefully wipe all oil from the resin areas? Is there an alternative finish that would suit a wood/epoxy mix better? In an ideal world it would be food… Read more »

Hi Eric, I have a tigerwood deck, in the Midwest, just put in Nov. 2017. Followed the instructions, and oiled with Ipe. It’s stayed tacky. Nevertheless, I cleaned the deck with mild soap and water and applied a coat of Thompson’s clear teak wood oil. Trying something different hasn’t worked after doing tons of research. This oil is not trying. Leaving the deck slippery in places, bubbling product in some, which I can scrape off like a film, and did absorb in some areas. It gets full sun. Any suggestions on what to do? I’m at a loss after tons… Read more »

HI Eric, we recently sanded down our patio furniture (world market stuff, eucalyptus)… we love the light natural look but everything we have applied has darkened it. What do you suggest using to maintain it’s current look without shiny or dark results.

Every single finish will darken the wood to some extent because it is, in essence, “wetting” the grain of the wood. Best bet would be to bleach the wood to a lighter color, then finish.

have white oak timbers that will be outside year round. any ideas what to use for best protection?

Great article! Thank you! We’re trying to work out how to finish a new sapele handrail to our staircase. We were leaning towards lacquer but wondered what would you recommend?

So I just shellacked a window sill that occasionally gets water on it (did not realize how that could be an issue) …is there anything I can use OVER the shellac to protect it from water damage? Really don’t have the time to start over…used it because it was quick. And it matched up beautifully.

Shellac can be topped with varnish.

Mike

Great article. We have a Sapele balcony which is untreated and has been through a tough winter in London by English standards. It’s faded and need restoring and oiling. Any advice on what products to use?

Thanks

Yogi

Excellent, excellent article…among the clearest and best explanations, in short, of finishes!

Eric, I realize any knowledgeable person will probably shake their head and say I’m an idiot for asking, but here goes: – I have several poplar trees and one pine tree that fell in a storm last month. – I cut the poplar trunks to 13′ lengths then split them in half lengthwise, each about 10″ in diameter. Each still has the bark on. ??? CAN I OIL OR VARNISH OR SHELLAC THESE AS THEY ARE WHILE THE WOOD IS STILL WET ??? – What about the pine stumps (24″ high and about 24″-36″ in diameter), also wet? I am… Read more »

Chances are, the wood is still very wet. A lot will depend on your desired end goal. If you work with the wood now, it is inevitable that the wood will shrink and deform as it continues to dry out. The idea would be to have this process happen before you work the wood into its final shape rather than after.

Hi Eric, thank you very much for great info. I have a balcony floor that needs help. I would love the teak finish look with the shine look. I would greatly appreciate your input.

Thank you

Maybe something like a glossy spar urethane?

I have a large piece of old mahogany that my wife would like as a work top in the laundry room. I have sanded with several grits and now looking for a finish. I have some Epifanes varnish for durability. Is it ok to apply a couple coats of Tung oil first? I had a concern about adhesion. Or should I just use the varnish? Also should I apply a thinned down varnish on the first coat?

Amazing article, Eric! What kind of coating would you recommend for a matte-finish? Specifically one that is environmentally-friendly, if there’s an option. Let me know, thank you!

It all depends on what level of protection you’re looking for, and how large the project is. I like “Tried and True Varnish Oil” for an all-natural finish that’s non-toxic. It’s basically just linseed oil and a few other ingredients.

which finish you recommend over a pure TUNG OIL table, that maintains it’s Iridescence? Will poly give it a flat plastic look?

this walnut table has coats of pure tung oil (mixed with citrus solvent for thinning).

How would you retain this “Iridescence”, while providing some scratch resistance?

Will polycrylic make it look plastic?

Or stick with sealer, then top with lacquer?

Does any of this information apply to wood veneer or is it only relevant to solid wood?

I am making replicas of 18th century trade knives using curly maple for handle scales. Will using boiled linseed oil or tung oil provide reasonable wear protection for the handles?

I have new Mahogany to install for a porch railing. Top and bottom rails, balusters and end plates. There is some sun protection, maybe 50/70%. I’ve seen some good about using raw linseed oil as the sealant/preservative. What do yo think? I don’t care about maintenance (redoing), or long dry time.

Ive got some hand made chess pieces made from ebony and lemonwood (at least thats what they called it). Its a veri light wood with a very slight tint of green. The pieces are all raw and I wanted to protect them. Mainly keep the raw finish and preserve the light color.

I was originally thinking oils but not if it will yellow or change the original color. Definitely avoid gloss and preserve the flat texture if I can.

If they are raw wood, any finish (even a wax) will darken the wood somewhat as the wood fibers absorb the finish. But I’d say if you are planning on actually using the chess pieces, it’d be better to finish them and avoid oils from people’s hand absorbing in the wood in select places instead. If you want a relatively non-yellowing oil, I’d go for polymerized (not raw) tung oil.

Polycrylic finish goes on clear without darkening the wood. I have used it on box elder for that purpose. It’s water-based, easy to use, low odor, very tough, and dries fast

I am refinishing an old (1940s?) oak machinist’s tool chest that belonged to my husband’s uncle. I don’t know what the original finish is, but it has worn off in places, has some old white water stains, and some areas with black grease or oil stains. It also has a very strong and unpleasant musty odour. In short, it is a mess! I am thinking I will try to remove the old finish by sanding, before resorting to a chemical stripper (as it’s too cold to work outside with proper ventillation). I am not sure what to use to refinish… Read more »

In my opinion, it’s hard to beat shellac for odor-blocking ability (such as Zinsser’s Seal Coat). Maybe it’s not the best for a durable top coat, but for light wear it should be fine. I don’t think an oil finish would do much to block odor, though with something like tung oil it might replace it with its own scent! I’d go easy on the wearing/moving surfaces and not apply too much finish. Also, if using shellac, keep in mind that it dries to a high sheen when built up in layers as a film finish (which would be what… Read more »

Thanks, Eric, for the very helpful article and advice. I just have a couple more questions:

I see that Zinsser sells both a “Bulls Eye Shellac – Traditional Finish and Sealer” and a “Bulls Eye SealCoat Universal Sanding Sealer”. Do you think either would do for my project? Also, can you stain the wood before applying the shellac finish?

I’d use the SealCoat, it’s basically a slightly thinner version of the shellac, which is much easier to apply and work with. Yes, you can use a stain under the shellac.

Marie. For many years I laid / finished hardwood floors, one problem we had was finishing around areas where machinery had been , these areas had typically mineral oil staining . The problem was solved by sanding and immediately put a coat of shellac over it on drying could be sealed normally.

Very informative article… What would be the best finish/sealer for a 34″ X 15″ (3/4″ thick) stain grade solid wood panel that will go under my television? I plan to use a dark stain. Some of the wood will show. I’m leaning toward shellac but I’ve heard that shellac leaves an odor (I live in a small apartment). Once the TV’s in place, I don’t want to have to move it again to retreat the wood. As a newbie, I’m looking for something that will do the job but easy to work with… Thanks.

Shellac is quite the opposite, it masks and seals in odors well — and while the alcohol in shellac has a strong smell when you are applying it, there is absolutely no odor once finished.

If you are just using products from a home improvement store, I’d go with a wiping polyurethane for a good balance between toughness and ease of application.

Eric, Great article – very helpful – thank you! Please see the attached photo. I am siding the inside of a 175 square foot bedroom to make it cabin-like, using tongue & groove, kiln dried pine (white, we believe). I want a “natural” yet yellow/golden/honey finished appearance, like the chairs in the picture. I have been advised to spray a 70% polyurethane / 30% lacquer thinner mix, but am concerned about gumming up & damaging my sprayer, and how long an odor from the poly might last. I am looking at an option of boiled linseed oil, rubbed on. The… Read more »

I have a question. I am thinking of planking my wall. If I use a hard wood such as Hickory or maple do I need to finish it. or could I just use the natural wood. I have base board heating

I would still apply a finish. Even if a wood is hard, it will still soak in and be stained by things that happen to come into contact with it.

Wow, I had no idea that so much had to be taken into consideration when choosing the right finish for wood. I had always been under the impression that varnish was the best option because my father always used it, but it is nice to learn about some of the others. I’m especially impressed by some of the specialty finishes as I imagine that they can provide quite a unique and interesting look.

What would you suggest as a finish for a cherry book case that will have an oil-like appearance and won’t be absorbed by any of the paper or books?

I’d just use Boiled Linseed Oil and allow it to fully cure/dry before using it.

I’m going to be working on a staff that might be taking a beating as a melee weapon as well as a walking stick. I’m curious about a durable yet beautiful finish for oak wood?

I’d recommend an exterior grade spar urethane finish. It’s tough, but not super-hard. It’s almost counter-intuitive, but the softness of the spar urethane actually gives an added resilience and scratch resistance that “harder” finishes lack. I’d call it “tenacious” rather than “rock-hard” — which is a good thing in this instance.

If a butcher block top has been treated with mineral oil is there a way to sand it down and then use another finish? How deep of a sanding would be necessary? I see the comment above that the Tung oil over the mineral oil is not recommended.

I’d love some advise. Having an ash dining table made. We love the light ash tone. When the maker brought finish samples most look too yellow for me. Of the choices he gave danish oil & teak oil which were the most natural but still not as white.

Any suggestions for other finish?

You could use a water-based polyurethane to keep the light color and avoid yellowing. If you want it to be lower key, I’d suggest using either satin sheen for the poly, or else just use gloss and then rub it down with #0000 steel wool afterward.

My husband and i just had our ash trees lumbered for hardwood floor in our new house. We just laid the floor it is beautiful but i ddnt know which way i should finish them, any ideas anyone? Margie

Thanks for the interesting rundown on what’s out there, Eric. This year I expect to install a basement ceiling of pine beadboard, about 800 board feet of it. There’s plenty of plumbing overhead, of course, so I’d like to guard against the beadboard becoming water-stained if we ever have a leak. I’m thinking it would make sense to finish the boards before they go up, as long as I’m not using a finish that takes forever to dry. After reading your article, I’m thinking of either spraying lacquer or applying some kind of oil with a rag. What do you… Read more »

I’d say it depends on how much work you want to put into it. If protection and stain resistance is paramount, I’d spray a few coats of lacquer on both front and back. But I’m guessing that if you have a water leak, you probably won’t know about it or discover it until it’s too late. For all practical purposes, there isn’t really a wood finish that would totally prevent staining if the wood is exposed to water long term. I’d use whatever is easiest and most cost effective — the only reason to use film building finishes would be… Read more »

I guess Bees Wax is just not new enough to deserve a mention? as in “no commercial potential”?

Good luck I’ve had mixing equal parts of tung oil, beeswax, and turpentine. Very nice satin finish, good feel and fragrance. I always add a dryer to tung oil in any application. Dries much quicker, i.e., several hours. Wet sand in tung oil cut~ 10-20 % with turpentine. I use a lot of drier, maybe 10-20 % of the mix. Drier can be purchased in an art supply store. It is often added to oil paint.

Thank you for this breakdown. It is so hard to find good comparisons on wood protection/finishes. I am still a little unsure of my decisions and hoping you can help with further guidance. We just installed American Walnut butcherblock countertops in our kitchen and are having a hard time figuring out the best way to protect and maintain them without taking away the beautiful natural look of the wood. We considered Waterlox, but even with a “low-gloss” option I was very worried about having a shiny countertop and needing to strip the finish and risk messing up the wood so… Read more »

That sounds like a bad idea. Mineral oil is non-drying. Putting a drying oil over a non drying oil sounds like a great way to get a crinkle finish.

Hi there,

Great article! I have bought some reclaimed wood that I plan on using in my workshop as shelving. The wood was roughly sanded and the planks glued together by the man I bought them from. I love the natural colour of the wood and I would prefer to leave them as they are.. is this ok for the wood for do they need some kind of treatment? Would they dry out and deteriorate over time? They are in a room that is well insulted and warm (a garage conversion). Thanks for your help!

As long as they are kept away from rain/water, they should be fine.

Thanks for your reply! I think I’ll do one coat of a shellack sanding sealer and leave it at that!

I’ve always been partial to a mix I call LTV. Equal parts linseed oil, turpentine, and varnish. Soak the wood well and let it drink all it wants, then wipe. The finish/patina gets deeper as time goes by.

Thank you very much for this synopsis! I am a total newbie to all of this, but have purchased 360 sq ft of reclaimed barnwood to create two accent walls in my basement. After reading your article & many others, I’m trying to decide between mineral, linseed & rung oils or some combination thereof. I only want to enhance the character of the wood & darken it just enough to do so. I’m also concerned with any effect the oil will have on the air quality of the basement. Suggestions would be much appreciated!

If it were me, and I wanted to minimize lingering odor, I would just apply a coat of thinned shellac and call it a day. Yes, the alcohol in shellac does have a strong initial odor, but it dissipates very quickly once applied. There is a sanding sealer available at most hardware stores that goes by the name Zinsser SealCoat that should do the trick. Just be careful not to apply multiple coats, as once shellac starts to build up a film finish it shows its glossy character. But one simple seal coat should remain flat.

Hi Suzie . . . I have a similar project with reclaimed wood, redwood, I think. I’m wondering what option you went with and how it turned out. I want a flat finish on my wood, but with the grain accented.

The answer for your question on this forum recommended shellac, but in my experience, lacquer, which is a similar evaporative finish, dries much more flat, without the sheen that even one coat of shellac has. I would be interested to know how your project turned out?

I’ve had great luck with Waterlox Tung Oil. It’s not cheap and they do have some mystery formula, like the article here states, with their own combination of resins and tung oil, but what a finish. It takes a while to dry – a few weeks to actually cure – but looks very good and is a penetrating, hard, durable finish. Great on floors or counters you don’t mind looking darker.

I have had great results on turning projects by starting with Superglue for one coat, resanding and then using shellac. I have never had a chip or dulling problem and the finish seems to get tougher with age.

I just ordered I huge 54″x112″ butcher block top for my island. It came raw and the people there said to use mineral oil. They gave me as a gift a small chop block. I went to Lowe’s and they suggested a wood polish and conditioner made of beeswax, carnuaba wax and orange oil. I sanded my small block down then when it was very smooth i added this with a cloth and let it sit for a night and a day. I used it today and washed it with water and a sponge and it became scratchy. What did… Read more »

My wife and I used waterlox tung oil on our rock maple kitchen counters, three years ago. The company claims it’s safe and it has lasted…and looks good. Took two days to cure enough to use. Smells like something the dog dragged in, but just for a day.

I used mineral oil on ours. I love it.For the first week I applied it every day, then once a month for the first year. Check periodically for dryness, can apply as needed.

what would you recommend for an engineered veneered product ?.

Great article, especially for us long time workers of wood who still consider finishing to be a black art.

Good article, Eric. For those out there who haven’t yet discovered (often the hard way) the drawbacks, It might be nice to add a bit about NOT mixing substances or techniques.

FWiW, after using lacquer, unless I got a deck to cover, I’ll never use woodstain again!