by Eric Meier

There seems to be a lot of confusion surrounding a certain type of wood called satinwood. The very name satinwood, much like teak or rosewood, is what I would call a halo wood name, and is frequently used (or potentially abused) by wood retailers. Let’s see if we can’t sort out this confusion, and get to the bottom of the matter.

What is Satinwood?

Most likely, the origin of the term comes from the woven fabric satin, which has a smooth, lustrous face, and is known for its loose, flowing folds. With this baseline definition of satin in mind, let’s look at the world of satinwood. In addition to loosely resembling satin fabric, there are a few other characteristics in boards and veneers that are traditionally expected in order for a wood to be considered satinwood.

Satinwood attributes

Yellow/gold color—Since the original species of satinwood (described below) were yellow colored, this has become the expected color for satinwood. One exception: bloodwood is sometimes called red satinwood.

High natural luster—In keeping with the similarity to the fabric, any wood seeking to bear the satinwood name should have a naturally lustrous and chatoyant surface. In fact, satinwood veneered furniture usually has such a unique look and depth that it can be very difficult to repair, even with very similar pieces. [1]Varese, M., (1983, June 30). Satinwood: Repairs can be noticeable. New York Times.

Interlocked/figured grain—Along with the natural luster, the grain should have a fair degree of figure and visual depth in order to help give a more three-dimensional appearance. Quartersawn surfaces will usually have a strong ribbon-stripe figure.

Fine textured—In my opinion, this is the characteristic that’s most frequently neglected in the new and aspiring would-be satinwoods. Oftentimes, they have large pores, giving a coarser, less smooth texture overall.

High density/hardness—Perhaps not an absolute necessity, especially since so much satinwood occurs as veneer. But the original species of satinwood tended to be quite heavy and hard, certainly a fair degree heavier than common cabinet hardwoods like maple or oak.

Will the Real Satinwood Please Stand Up?

Despite a number of woods going by the satinwood name in one form or another (usually in combination with a geographic location), it helps to start with historical use as a baseline. Regardless of recent trends or marketing campaigns, there’s been only two predominant species of satinwood that have been accepted as satinwood in its truest sense, and both are in the Rutaceae (citrus) family.

The original article.

West Indian Satinwood (Zanthoxylum flavum)

Distribution: Caribbean

Tree Size: 30-40 ft (9-12 m) tall,

1-1.5 ft (30-46 cm) trunk diameter

Average Dried Weight: 56 lbs/ft3 (900 kg/m3)

Specific Gravity (Basic, 12% MC): 0.71, 0.90

Janka Hardness: 1,820 lbf (8,100 N)

The Backstory: This wood was the original satinwood. In the absolute strictest sense, this is the true first historical species. It’s all but gone now, at least in a commercial sense. It was harvested at such a frenzied and unsustainable pace in the 1800s, that it has more or less been off the market for centuries now.

The (backup) original article.

Ceylon / East Indian Satinwood (Chloroxylon swietenia)

Distribution: Central and southern India, and Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon)

Tree Size: 40-50 ft (12-15 m) tall,

1-1.5 ft (.3-.5 m) trunk diameter

Average Dried Weight: 61 lbs/ft3 (975 kg/m3)

Specific Gravity (Basic, 12% MC): 0.80, 0.98

Janka Hardness: 2,620 lbf (11,650 N)

The Backstory: With the exhaustion of the original species, a replacement was sought and found in this eastern species. What began as a mere substitute, having now tallied over a hundred years of use, has more or less become the highly regarded de facto standard that most regard as genuine satinwood. It’s still a very rare and valuable wood today, but it’s not the impossible-to-find West Indies species that’s been commercially unavailable since the 1800s.

Common traits found in both original species

- Although the eastern variety tends to be slightly heavier on average, both woods are very heavy at 56-61 lbs/ft3 (900-975 kg/m3)—weight alone should not be used to distinguish the two species.

- Both species are in the Rutaceae (citrus) family, though in separate genera.

- Both woods have a very fine texture and small pores which don’t require filling during the finishing process.

- Both woods have a faint yet pleasant scent when worked.

- Both woods have a pronounced blunting effect on cutters and can be challenging to work with.

- Both woods are very expensive and rare—though the West Indies variety is much less commonly seen, and most wood listings claiming to be of the western type are usually from careless sellers who have misapplied the wrong scientific name to their “satinwood.”

- The two woods have a very similar appearance, grain figure, and anatomy, and can be very difficult to tell apart. See my comments on distinguishing the true satinwoods for specific advice on this.

Next, let’s go over the other woods that have also been sold and offered under the name of satinwood.

Aspiring “Satinwoods”

Sidenote: This section was formerly titled “The Impostors,” but I felt that was a bit too harsh. It’s not my intention to disparage the following woods listed below, but instead to simply point out the sometimes deceptive common names these woods are given. These are by-and-large quality hardwoods, suitable for many projects—but it can create a lot of confusion for buyers when they are sold as satinwood.

Pyinma (Lagerstroemia spp.)

Distribution: Southeast Asia

Tree Size: 40-65 ft (12-20 m) tall,

2-3 ft (.6-1 m) trunk diameter

Average Dried Weight: 44 lbs/ft3 (705 kg/m3)

Specific Gravity (Basic, 12% MC): 0.55, 0.71

Janka Hardness: 1,090 lbf (4,850 N)

Sometimes sold as: Asian satinwood, Cambodian satinwood, or (worst of all) just “satinwood.” This wood is the chief offender!

Where it falls short: Pyinma is about 20% lighter than genuine satinwood. And since it’s a semi-ring-porous wood with larger pores, it also has a coarser and more uneven texture. The color can sometimes be darker and more variable than true satinwood.

To be honest, it’s not all bad with pyinma, so long as you are not expecting an exact or historical satinwood replacement. It does not have the same blunting effect on cutters as true satinwood. Pyinma is a very economical alternative to true satinwood.

Perhaps the most notable characteristic of pyinma is it’s outstanding curl. Nearly every piece of pyinma has some level of curly grain, ranging from light to very deep and figured, perhaps the “curliest” of all woods! This wood is almost always sold in solid lumber or turning blank form.

Movingui (Distemonanthus benthamianus)

Distribution: West Africa

Tree Size: 100-125 ft (30-38 m) tall,

3-5 ft (1-1.5 m) trunk diameter

Average Dried Weight: 45 lbs/ft3 (720 kg/m3)

Specific Gravity (Basic, 12% MC): 0.58, 0.72

Janka Hardness: 1,280 lbf (4,850 N)

Sometimes sold as: Nigerian satinwood, African satinwood, ayan.

Where it falls short: Similar to pyinma, movingui is about 20% lighter than genuine satinwood. It also has larger pores than satinwood, giving it a slightly more coarse texture (though unlike pyinma, the texture is even and movingui is a diffuse porous wood).

In terms of appearance, movingui is probably the closest to satinwood of all the aspiring satinwoods, with a nice consistent golden color, an interlocked grain that can be highly figured, and good natural luster. Unfortunately, another similarity with satinwood is that movingui has a pronounced blunting effect on cutters due to its high silica content.

Movingui is usually sold in veneer form, but it’s not uncommon to see the wood available as solid lumber as well. Prices tend to be in the mid to upper range for imported lumber, though not as expensive as true satinwood.

Yellowheart (Euxylophora paraensis)

Distribution: Brazil

Tree Size: 100-130 ft (30-40 m) tall,

3-5 ft (1-1.5 m) trunk diameter

Average Dried Weight: 52 lbs/ft3 (825 kg/m3)

Specific Gravity (Basic, 12% MC): 0.67, 0.83

Janka Hardness: 1,790 lbf (7,950 N)

Sometimes sold as: Brazilian satinwood, pau amarello.

Where it falls short: Yellowheart usually lacks the strong and tight grain figure that’s so commonplace in both satinwood and its lookalikes. More commonly, there are wide, undulating curls better suited to larger panels rather than smaller intricate grain figure that satinwood is known for. The texture is also just a bit coarser and more porous, with yellowheart having larger pores, but that’s splitting hairs a bit.

Technically, yellowheart is in the Rutaeae family like the true species of satinwood, but this is a wood that’s already had a bit of an identity crisis: initially it was called by its Portuguese name pau amarello, meaning “yellow wood.” Now it’s been given a new (more commercially profitable) name, yellowheart. Hence, it’s not too frequently called Brazilian satinwood anymore.

Yellowheart is about the same weight as true satinwood, and it also takes a nice polish and has a good natural luster, just like satinwood. The wood is used almost exclusively in lumber form, and is quite inexpensive for an imported species.

Avodire (Turraeanthus africanus)

Distribution: Western and central regions of Africa

Tree Size: 80-115 ft (25-35 m) tall,

2-3 ft (.6-1.0 m) trunk diameter

Average Dried Weight: 36 lbs/ft3 (575 kg/m3)

Specific Gravity (Basic, 12% MC): 0.48, 0.58

Janka Hardness: 1,170 lbf (5,180 N)

Sometimes sold as: African satinwood, white mahogany.

Where it falls short: Avodire is significantly softer and lighter than true satinwood. The grain is slightly more coarse with slightly larger pores.

Being in the Meliaceae (mahogany) family, avodire is actually more closely related to true mahogany than satinwood, and it is sometimes called white mahogany (though this common name is also applied to other woods, such as primavera and an Australian species of Eucalyptus as well).

Much like movingui listed above, avodire is an African species that can have very stunning grain patterns, rivaling true satinwood. The wood is most commonly seen as figured veneer, but solid pieces are sometimes available as well, though on the whole they tend to be less figured than the veneer. (It’s not uncommon for the best logs to be made into veneer rather than getting sawn into timber.)

Afrormosia (Pericopsis elata)

Distribution: West Africa

Tree Size: 100-150 ft (30-46 m) tall,

3-5 ft (1-1.5 m) trunk diameter

Average Dried Weight: 45 lbs/ft3 (725 kg/m3)

Specific Gravity (Basic, 12% MC): 0.57, 0.72

Janka Hardness: 1,570 lbf (6,980 N)

Sometimes sold as: Benin satinwood, African teak.

Where it falls short: Afrormosia is about 20% lighter than true satinwoods, and has a more porous and open texture. On average, the color tends to be a darker orangish brown, but some select pieces can have the golden color of satinwood.

Like most other woods on this list, afrormosia is also available in veneer form, and can take on a number of different appearances depending on the grain orientation and color. Although not common, some pieces of afrormosia can have an interlocked and figured grain with a golden yellow color that bears a close resemblance to satinwood.

More often, afrormosia is billed as a substitute for genuine teak rather than satinwood, though it is sometimes sold under the name Benin satinwood.

Obeche (Triplochiton scleroxylon)

Distribution: Tropical West Africa

Tree Size: 65-100 ft (20-30 m) tall,

3-5 ft (1-1.5 m) trunk diameter

Average Dried Weight: 24 lbs/ft3 (380 kg/m3)

Specific Gravity (Basic, 12% MC): 0.32, 0.38

Janka Hardness: 430 lbf (1,910 N)

Sometimes sold as: soft satinwood. (At least the name is infused with appropriate modesty!)

Where it falls short: Just as the name implies, obeche is an extremely soft and lightweight wood. Of all the woods labeled as satinwood, I think obeche is the farthest stretch. Not only because of its extreme softness, but because the wood lacks the dramatic figuring, and has large open pores, giving it a much more coarse and grainy texture.

Perhaps only obeche quartersawn or figured veneer could be mistaken for true satinwood. More often than not, it is used as a base and stained or otherwise colored for use in furniture and other interior millwork. On the positive side, the wood should be relatively inexpensive to obtain and free from environmental or sustainability concerns.

Other Satinwood lookalikes

While some woods may have a vague similarity to true satinwood (which retailers are eager to market), other woods may also share similarities, but for one reason or another, are never marketed as such. The following woods don’t tend to be sold as satinwood, but are nonetheless good candidates if searching for a similar appearing wood.

Primavera (Roseodendron donnell-smithii)

Distribution: Central America

Tree Size: 65-100 ft (20-30 m) tall,

2-3 ft (.6-1.0 m) trunk diameter

Average Dried Weight: 29 lbs/ft3 (465 kg/m3)

Specific Gravity (Basic, 12% MC): 0.40, 0.47

Janka Hardness: 710 lbf (3,170 N)

Sometimes sold as: blond mahogany, white mahogany. Not typically sold as satinwood, but does bear a strong resemblance in some veneer patterns.

Where it falls short: Much like avodire listed above, primavera is significantly softer and lighter than true satinwood. The grain is slightly more coarse with slightly larger pores.

Although this wood isn’t really marketed as a satinwood, the resemblance can be unmistakable in some cuts of veneer. Although the color can be more varied, in pieces with an even golden color, especially those with interlocked grain, the figure can be very similar to satinwood. Primavera is much more commonly available as veneer, though solid pieces are sometimes available.

While you’re not likely to encounter this wood if you are searching specifically for satinwood, it can be a worthy substitute if a decorative veneer with similar appearance is sought.

Anigre (Pouteria altissima)

Distribution: Africa (most common in tropical areas of East Africa)

Tree Size: 100-180 ft (30-55 m) tall,

3-4 ft (1.0-1.2 m) trunk diameter

Average Dried Weight: 34 lbs/ft3 (550 kg/m3)

Specific Gravity (Basic, 12% MC): 0.44, 0.55

Janka Hardness: 990 lbf (4,380 N)

Sometimes sold as: almost universally sold as anigre or other variant spellings such as anegre, aniegre, aningeria.

Where it falls short: Anigre is softer and lighter than satinwood. Additionally, the grain figure in veneers doesn’t always resemble satinwood, tending to have a straighter grain with less interlocking (usually lacking the accompanying figure that interlocking produces.)

Anigre is a figured hardwood with a following and reputation in its own right. Sold most commonly as veneer, anigre can have a wide variety of grain patterns, some of which can closely resemble satinwood. Overall, the color tends to be slightly redder or browner, with less gold or yellow coloration.

Sorting Them Out

If you have solid lumber:

Weight should be a very reasonable and accurate indicator to begin dividing lumber. If you can’t use a scale to weigh the wood, try to get a feel for the wood’s weight as compared to another known wood, such as red oak which as a baseline has an average dried weight of about 44 lbs/ft3 (700 kg/m3).

Lighter woods

Obeche 24 lbs/ft3 (380 kg/m3)

Primavera 29 lbs/ft3 (465 kg/m3)

Anigre 34 lbs/ft3 (550 kg/m3)

Avodire 36 lbs/ft3 (575 kg/m3)

Pyinma 44 lbs/ft3 (705 kg/m3)

Movingui 45 lbs/ft3 (720 kg/m3)

Afrormosia 45 lbs/ft3 (725 kg/m3)

Heavier woods

Yellowheart 52 lbs/ft3 (825 kg/m3)

West Indian satinwood 56 lbs/ft3 (900 kg/m3)

East Indian satinwood 61 lbs/ft3 (975 kg/m3)

After helping people identify wood for over a decade now, I can say unequivocally that people have a strong tendency to overestimate a wood’s weight, so keep that caveat in mind. And remember that wood density will vary by an average of +/- 10% of the weights listed above, so there’s enough overlap in many of these wood species to eliminate using weight as the sole means of identification. Also, these weights are listed for dry wood; if you have a turning blank that’s still green (pyinma is one such species that’s commonly sold in this form), then just about any kind of wood can potentially feel heavier than oak.

If the wood sample is noticeably heavier than oak

Assuming you’ve got an accurate enough measurement of the wood’s density (ideally with a scale), this leaves just three satinwood candidates, two of which are the real thing.

Look at the endgrain (preferably with a 10x magnifier). See the article on Hardwood Anatomy for descriptions of features.

- True satinwoods should have small to medium sized pores, along with marginal parenchyma (seen in the photo examples below as intermittent horizontal lines) at the boundary of each growth ring.

- Yellowheart, on the other hand, will have slightly larger pores, and a much more vague division of growth rings, with no parenchyma bands to mark the growth ring margins.

If the wood sample is light (about as heavy as oak)

Initially, if the wood is actually significantly lighter than even oak, you can immediately separate woods like obeche and primavera from the rest on account of their extremely light weight, which are about as heavy as basswood (Tilia americana) at 26 lbs/ft3 (415 kg/m3).

Additionally, anigre and avodire are two woods that are fairly light and not likely to overlap the heavier woods on this list, having a weight comparable to black cherry (Prunus serotina) at about 35 lbs/ft3 (560 kg/m3)

After this initial filtering, there are three primary contenders that have weights that are pretty close to red oak. Look at the endgrain (preferably with a 10x magnifier). See the article on Hardwood Anatomy for descriptions of features.

- Pyinma is ring-porous or semi-ring-porous, and will have varying sizes of pore openings, usually arranged in intermittent rows corresponding to growth rings. It also has extensive banded parenchyma, visible as pale-colored lines running parallel with the growth rings.

- Movingui has large to very large sized pores in no specific arrangement, and well-developed winged, lozenge, and confluent parenchyma patterns, sometimes seen in bands as well.

- Afrormosia has medium to large pores that are slightly smaller than movingui. Also, the parenchyma is a little less extensive, mainly just lozenge and confluent.

The above information can be helpful to use if you have raw lumber with access to weighing the wood alone, and/or looking at an unobstructed view of the endgrain. But many times, satinwood (or a wood with satinwood-like apperance) will occur in a finished furniture piece, or as a piece of veneer. In these cases, it can be much more difficult to identify the wood.

If you have veneer

Veneer is a much bigger challenge to identify because two very helpful features are more or less unavailable to us: weight and endgrain anatomy. All that we have to go on is the facegrain, so we will have to look at that very carefully and gather any possible clues to make an educated guess.

What we’ll be looking at on the facegrain is the pore width. Previously, we considered the pores on the endgrain, which appeared as tiny holes scattered throughout the end of the board. But now, we need to think of them more like tiny straws, and instead of looking at the ends of the straws as a holes, we’ll be looking at the facegrain and viewing the sides of the straws as thin grain lines running parallel to the wood fibers.

What we will be measuring is anatomically considered the pore diameter, but since it is viewed from the facegrain, it feels more practical to call it the the pore width, as it will be the width of the grain lines (like straws) we see from the face of the veneer.

How can we measure something this small?

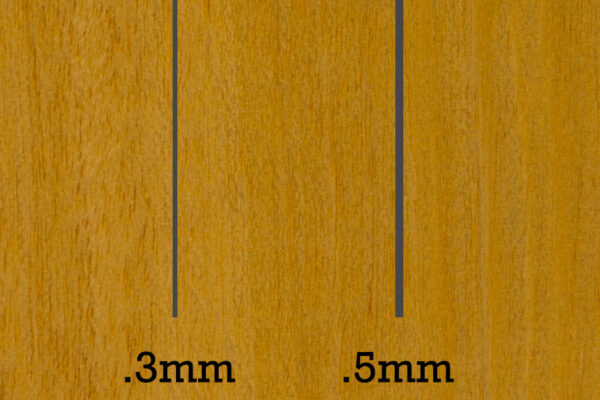

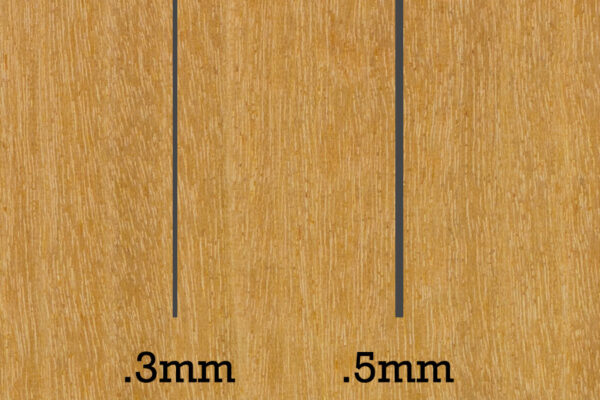

In wood anatomy, pore diameters are measured in microns. That’s pretty small. Without specialized tools and highly magnified views of the wood surface, it can be nearly impossible to get an accurate measurement this small. What we will do is use known small objects and get a good estimate of the pores’ comparative size.

Enter the mechanical pencil.

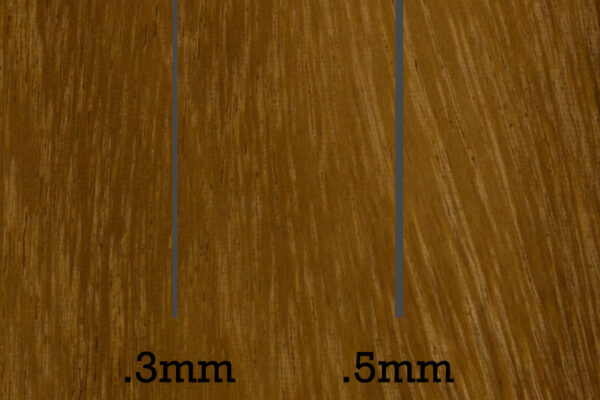

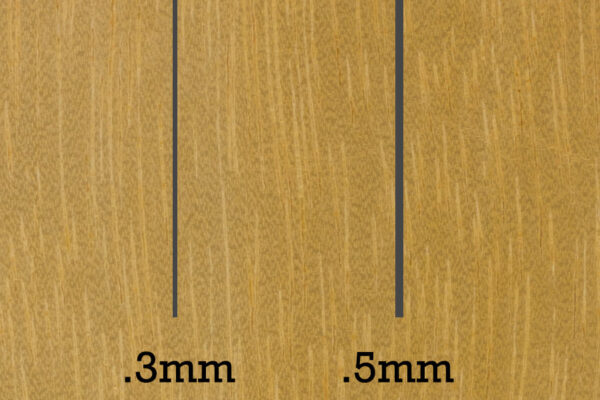

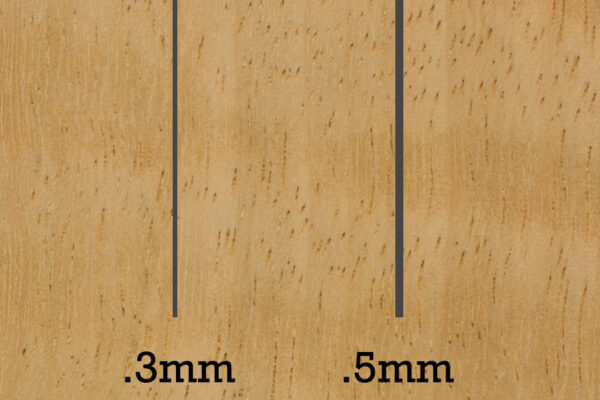

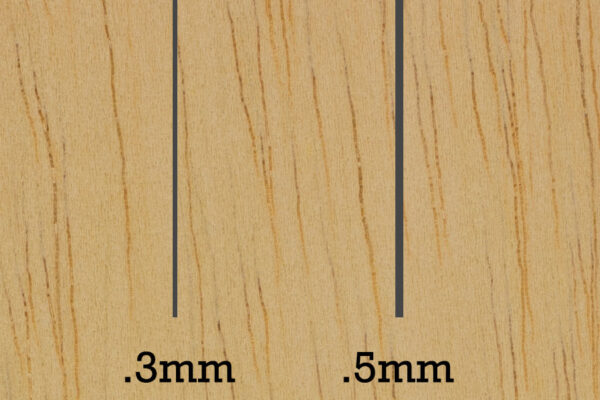

Most mechanical pencils have either .5mm or .7mm lead (and even better if you can find the smaller .3mm lead). There are 1000 microns in a millimeter, so we should hopefully have a baseline reference point to 300, 500, and/or 700 microns. (Admittedly, the .7mm lead will be much less useful and more difficult to estimate size from.)

Other possible ideas for reference material include electrical wire (using the very tiny inner strands, if the gauge/diameter is known), or a strand of hair. Hair can be more problematic since people’s hair thickness varies so much with ethnicity, so it isn’t always a reliable reference point.

With reference material in hand (the narrower the better), look as closely as possible at the face grain, and note the size of the pores. A magnifying glass is recommended.

Also note that on some woods and in some samples, the grain lines can be fairly difficult to see even under magnification. This is because some pieces have pores of a slightly contrasting color, usually appearing slightly darker than the rest of the wood, while other pieces can have pores appearing as lighter lines with very little contrast. The main thing to look for is the widest grain lines (where the plane of cut has effectively bisected very close to the exact middle of the straw-like pores whose diameters we are seeking to measure). If dealing with raw wood, it’s sometimes helpful to wet the wood surface slightly to increase the contrast between the pore lines and the rest of the wood fibers. Also, viewing the flatsawn areas of the piece with a cathedral-shaped grain patterns is usually easier to see grain lines in rather than viewing the quartersawn surfaces.

Satinwood Relative Pore Sizes

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Average Pore Diameter (µm) | Pore Diameter Range (µm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| West Indian satinwood | Zanthoxylum flava | 70 | 33-105 |

| East Indian satinwood | Chloroxylon swietenia | 75 | 50-100 |

| Afrormosia | Pericopsis elata | 110 | 80-150 |

| Avodire | Turraeanthus africanus | 143 | 100-185 |

| Movingui | Distemonanthus benthamianus | 180 | 120-255 |

| Obeche | Triplochiton scleroxylon | 250 | 200-280 |

Most data on pore diameter and range were taken from Delta Intkey.[2]‘Richter, H.G., and Dallwitz, M.J. 2000 onwards. Commercial timbers: descriptions, illustrations, identification, and information retrieval. In English, French, German, Portuguese, and Spanish. … Continue reading

Referring to the chart above, the reference material (such as .3mm pencil lead) can be used to get a better approximation of the pore diameter. It can still be difficult to get a precise measurement of the pores, but the reference material provides a good baseline, particularly when there are no other samples to compare it to, to ensure that the pores we are looking at are indeed “small” or “large” in the world of wood anatomy. See the subsection on pore size in the article Hardwood Anatomy for more information.

Reference Images with .3mm and .5mm pencil lead

If the veneer sample in question has a small or medium sized pores, and looks by all other outward indications to be a sample of satinwood, it may be very difficult to tell afrormosia from true satinwoods. But as a general rule, most veneer slices of afrormosia will be more of a golden yellow or a darker shade of brown, while satinwood ranges from bright yellow to golden yellow.

If the veneer sample in question has large to very large pores, pay close attention to color and figure. Movingui tends to be a bright golden yellow, with mottled and/or curly figure. Avodire can look very similar to movingui, but tends to be a paler yellow, frequently almost white, and with a weaker and more loose mottle figure. Obeche has the largest pores of the group, and the wood is pretty consistently a light yellow or white, and has almost no grain figure.

Distinguishing the true satinwoods

If you are fairly certain you have a genuine piece of satinwood, but would like to try to further narrow it down to one of the species mentioned above (either the West Indian or East Indian species), it can be very difficult to separate the two on the basis of appearance or macroscopic wood anatomy. However, here are two tips to help you make the distinction.

1. It is probably East Indian satinwood. Unless the piece in question is known to be dated back to at least the early to mid 1800s, the odds are simply much more in favor of the East Indian species, Chloroxylon swietenia. Just like in most courts of law where you are presumed innocent until proven guilty, it can be helpful to assume the more common East Indian type until proven otherwise.

2. Look closely at the ray structure. This can be difficult to examine because the rays themselves are almost the same color as the surrounding wood fibers, so it can be very hard to make them out at all, much less observe their pattern. For difficult situations, it can be better to go beyond a regular magnifying glass and use a 10x jeweler’s loupe to examine the rays. Also, wetting the grain (in cases of raw wood surfaces) can help bring out the contrast a little better.

Referring to the images above, if you look closely, you’ll noticed a subtle pattern in the East Indian satinwood (Chloroxylon swietenia) image. The rays occur as subtle variations of light and dark, and are arranged in orderly rows that form an almost fish-scale-like appearance in the wood. Conversely, the West Indian satinwood (Zanthoxylum flavum) image shows rays with a more or less random distribution, giving the wood surface a slightly freckled appearance.

This visual phenomenon is called ripple marks, and is discussed in the subsection on rays in my article Hardwood Anatomy. In summary, East Indian satinwood will exhibit ripple marks (though they can be very subtle and hard to detect), while West Indian satinwood will not.

Are you an aspiring wood nerd?

The poster, Worldwide Woods, Ranked by Hardness, should be required reading for anyone enrolled in the school of wood nerdery. I have amassed over 500 wood species on a single poster, arranged into eight major geographic regions, with each wood sorted and ranked according to its Janka hardness. Each wood has been meticulously documented and photographed, listed with its Janka hardness value (in lbf) and geographic and global hardness rankings. Consider this: the venerable Red Oak (Quercus rubra) sits at only #33 in North America and #278 worldwide for hardness! Aspiring wood nerds be advised: your syllabus may be calling for Worldwide Woods as part of your next assignment!

The poster, Worldwide Woods, Ranked by Hardness, should be required reading for anyone enrolled in the school of wood nerdery. I have amassed over 500 wood species on a single poster, arranged into eight major geographic regions, with each wood sorted and ranked according to its Janka hardness. Each wood has been meticulously documented and photographed, listed with its Janka hardness value (in lbf) and geographic and global hardness rankings. Consider this: the venerable Red Oak (Quercus rubra) sits at only #33 in North America and #278 worldwide for hardness! Aspiring wood nerds be advised: your syllabus may be calling for Worldwide Woods as part of your next assignment! References[+]

| ↑1 | Varese, M., (1983, June 30). Satinwood: Repairs can be noticeable. New York Times. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | ‘Richter, H.G., and Dallwitz, M.J. 2000 onwards. Commercial timbers: descriptions, illustrations, identification, and information retrieval. In English, French, German, Portuguese, and Spanish. Version: 9th April 2019. delta-intkey.com’. |

Fitting to the topic of satinwoods, do someone know the cause or characteristic what causes wood grain to have a natural good luster? I don’t mean that figured wood has an interessting way to reflect light, I mean regardless of figure. The more indepth the explanation is the better. I searched research paper for the causes of chatoyancy but this can’t be transfered to explain the difference in predestined wood luster.

I feel like searching for an eternty to answer my question. Thanks in advance.

It seems you have forgotten mentioning at list one African species, much more susceptive than Afrormosia. (a picture taken from one of wood-stock shops) This is Aningeria spp., also known as asanfena (Ghana), agnegre (Cote-d’Ivoir), Iandosan (Nigeria), mukali, kali (Angola), mukangu, muna (Kenia), osan (Uganda). I came to this info searching for what a ‘satinwood’ veneer I’ve been given (a friend of mine could not recall where it came from initially and what was the name) – and still I’m in doubt, my sample looks a lot like on the picture and in the same time similar to E.I. Satinwood… Read more »

this has been very interesting thank you very much,i live in Kuwait and found on a deserted Beach a large piece of timber 30 ft by 4-5 ft diameter as i am a wood carver i instantly started using it for some pieces i was commissioned for but could not identify it.now i know it is indian satin wood and very old…thanks again

Very interesting article as I have just aquired some satinwood veneer very very expensive for antique clock case renovation 1820s hardly any figure in it !! I would say beeswing is impossible to obtain in this country but fairly plentiful in america (I FIND THAT SAD) Great article

Thanks, really enjoyed the article. I am a knife maker in South Africa,

always on the look-out for hard woods with a close, tight grain, with a

high finished lustre. See attached photo of African sneeze wood –

Ptaeroxylon obliquum. Very hard and dense, and requires no sealing.

Polished to a high lustre. Unfortunately, very difficult to come-by.

I was just reading the article and saw your Movingui. Here is a picture of a set of 1911 45acp handgrips that a friend of mine made out of Movingui. There is a deffinate oriental pattern that emerged after he finished the grips.

Thanks, really enjoyed the article. I am a knife maker in South Africa, always on the look-out for hard woods with a close, tight grain, with a high finished lustre. See attached photo of African sneeze wood – Ptaeroxylon obliquum. Very hard and dense, and requires no sealing. Polished to a high lustre. Unfortunately, very difficult to come-by.

very enlightening and most interesting. regards david