by Eric Meier

by Eric Meier

Perhaps no term is more broadly applied and nearly universally accepted in the world of wood than that of cedar. Sure, there are hopeful terms such as rosewood or mahogany applied to misfitting woods like a glass slipper on one of Cinderella’s step-sisters, but that’s not quite the case with cedar. Despite more than a dozen or so cedar species coming from a number of divergent genera including both softwoods and hardwoods, there seems to be far less rancor and controversy as to what is (or is not) a proper cedar species.

[image credit: Cedar of Lebanon vase by Steve Earis]

Yes, but what kind of cedar?

Given the broad acceptance of the cedar label, the term can sometimes bring confusion when no qualifying adjectives (usually a color or locality) are used to describe it. For instance, instead of referring to a birdhouse made of eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), one might simply say that the birdhouse is made of cedar without specifying the type. In these cases, it becomes helpful to learn how to tell different species of cedar apart.

Hallmarks of cedar wood:

1. Cedar is aromatic. Simply put, the stuff smells good. I have been (and remain) incredulous of any attempts to boil all the manifold odors found in the different cedars of the world into one typified cedar smell. The scents of the various cedars are as different as the tree species themselves. Additionally, although there are a lot of woods that have a characteristic odor, that of cedar tends to linger much longer than most other woods.

2. Cedar is rot resistant. This can vary with each species, but on the whole, the wood of most cedar species are considered at least moderately durable in terms of rot resistance, and are frequently used for exterior applications.

3. Cedar is relatively lightweight and soft. While there may be a little bit of variation from one end of the spectrum to the other, on the whole, one common expectation is that cedar will be lightweight and generally cooperative when it comes to working with tools.

4. Cedar is (commonly) reddish brown. There are obvious exceptions such as Northern white cedar or yellow cedar (their names say it all), but on the whole, cedar is usually a predictable color and grain. While all wood has a natural charm and beauty, cedar definitely falls more into the “it’s-what’s-on-the-inside-that-counts” camp than some of the flashier woods such as rosewood.

5. Cedar tends to be somewhat dimensionally stable. I list this last, as it is perhaps not accurate to apply to all species of cedar, but it’s a common trait shared by many of the species. With changes in humidity and moisture content, a lot of cedar species have the virtue of not shrinking or swelling much—and when they do, they tend to do so in a uniform fashion (which is generally attested to by their low T/R ratios).

TL;DR (Too long; didn’t read) Sidenote for cedars of North America

I’d venture to guess that in 90% of instances for those located in the United States or Canada, the cedar in question can be immediately narrowed down to just one of two species. While regional exceptions and outliers certainly exist, there are two very common cedars used on a commercial scale in North America, and thankfully, they’re pretty easy to tell apart.

Color:

- Golden or light brown? It’s probably #1 (WRC)

- Darker reddish brown with an almost violet hue (sometimes with lighter patches randomly mixed in)? It’s probably #2 (ERC)

Odor:

- Reminiscent of sharpening wooden pencils? #1 (WRC)

- Reminiscent of birdhouses and closet liners? #2 (ERC)

Size/condition:

- Ginormous 6×6 rough-sawn posts, 2-by construction lumber, or dog-eared fence pickets? Usually #1 (WRC)

- Full of knots and processed as tongue and groove or thin boards? Usually #2 (ERC)

Tier 1: Cedar according to the stickler

Trees in the Cedrus genus. This includes only a narrow handful of species, and these are found only in a few spots on the globe—in the Mediterranean and Himalayan regions. Other so-called cedars found in continents such as North and South America, Australia, as well as very large swaths of Africa, Asia, and Europe, all fail to make the cut as true cedars[1]Pijut, P. M. (2000). Cedrus-the true cedars.—at least, according to the stickler.

SIDENOTE: Saving the world from botanical fallacy?

In an effort to prevent the uninformed masses from calling anything but Cedrus species cedar, the common names of all non-Cedrus species get second-class treatment, being called by compound or hyphenated names (e.g., red-cedar or redcedar), or even more directly by being called false cedar,[2]Oregon State University. (n.d.). False cedar genera. Common trees of the Pacific Northwest. Retrieved April 27, 2022, from https://treespnw.forestry.oregonstate.edu/conifer_genera/false_cedars.html to help distinguish them from those that are deemed worthy of the standalone cedar name. However, those that insist on this strict naming scheme do so at the peril of ignoring centuries (millenia, actually) of common usage to the contrary. (It is my personal opinion that common names, with all their quirks and inconsistencies, is not even a proper place to assert or deny a species’ validity—this is best left to the Latin binomial name—and accordingly, I have consistently endeavoured to deemphasize or even omit such hyphenated or compound names on this site whenever possible.)

Putting it all into perspective: In 1757, German botanist Christoph Jacob Trew formally described a genus of conifer trees, and he simply used the Latin name Cedrus, which comes from the Greek word kedros—what we know today as cedar. But ironically, in antiquity the name was commonly used to describe aromatic trees from the Juniperus genus. For example, the first century Roman author Pliny the Elder wrote in his Natural History of cedrus trees and mentioned their berries—but the Cedrus species that Trew described do not have berries, and the reference was more than likely referring to the trees of what we today call the Juniperus genus, which do have berries. Herodotus also made a historical reference to “cedar oil” in the fifth century BC, which was predominantly made from what we would today call species of juniper and cypress.)

Bottom line: With thousands of years of momentum, many species of Juniperus and Cupressus have just as much of a historical right to be called true cedars as those found in today’s Cedrus genus.

Sidenote aside, there are between two and four Cedrus species depending on different authors. All of them bear common names based upon their geographic occurrence. The two primary, more or less undisputed species are:

- Cedrus libani (Cedar of Lebanon)

- Cedrus deodara (Himalayan cedar)

Additionally, there are two other species that are sometimes treated as subspecies under C. libani by some sources, which are:

- Cedrus atlantica (Atlas cedar)

- Cedrus brevifolia (Cyprian cedar)

Identifying Cedrus species

Scent is very often crucial in identifying cedar species. The only problem is, scent can be very subjective and very difficult to describe in mere words. Sometimes it helps to have known samples as a point of reference.

Cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani)

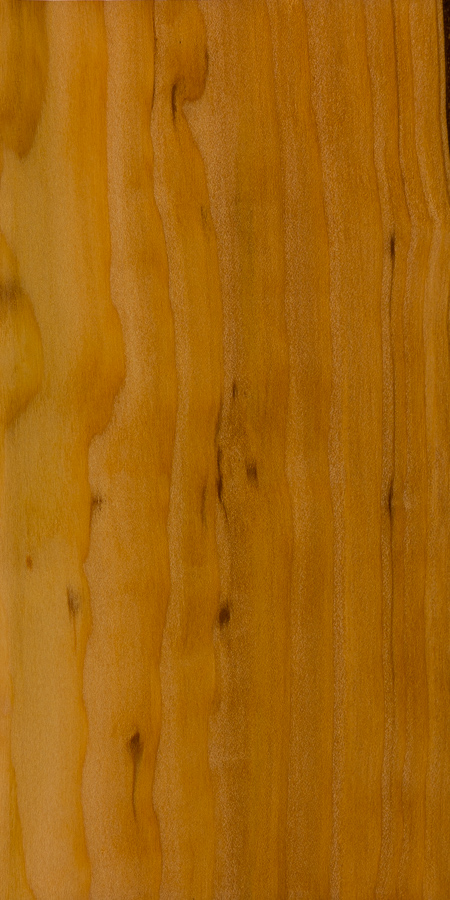

Drag the slider up/down to toggle between raw and finished wood.

Odor: All Cedrus species share a sweet, rather citrus-like scent that lingers well after the wood has been cut or machined.

Appearance: The color tends to be a light reddish brown, usually with moderate to widely spaced growth rings. Finished wood can age to an orangish brown.

Availability: Cedar of Lebanon and its kin aren’t really commercially available in any appreciable scale anymore. However, sometimes landscape or ornamental trees (particularly those that have been storm-damaged) can provide very limited supplies of wood.

Lookalikes: Since Cedrus species tend to be rather light colored, it could conceivably be confused with other tier-2 species of lighter-colored Cupressaceae cedars—including many Cupressus species, as well as Northern White Cedar (Thuya occidentalis), and a number of lighter-colored cedars in the Chamaecyparis genus. Besides using scent to distinguish among the species, look at the endgrain and check for zonate parenchyma—Cedrus is not known for having much observable axial parenchyma.

Tier 2: The Family Cupressaceae, worthy of the cedar namesake

Tier 3: Hardwoods in the Meliaceae family, close enough?

Tier 4: Miscellaneous aspiring cedars

References[+]

| ↑1 | Pijut, P. M. (2000). Cedrus-the true cedars. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Oregon State University. (n.d.). False cedar genera. Common trees of the Pacific Northwest. Retrieved April 27, 2022, from https://treespnw.forestry.oregonstate.edu/conifer_genera/false_cedars.html |