DATA SOURCE(S): 27,30,36,39,43

Common Name(s): Quebracho, quebracho colorado santiagueno, red quebracho

Scientific Name: Schinopsis lorentzii (syn. S. quebracho-colorado, S. hakeana)

Distribution: South America (primarily Bolivia, Paraguay, and Argentina)

Tree Size: 40-80 ft (12-24 m) tall,

2-4 ft (.6-1.2 m) trunk diameter

Average Dried Weight: 75.3 lbs/ft3 (1,205 kg/m3)

Specific Gravity (Basic, 12% MC): 1.02, 1.21

Janka Hardness: 3,530 lbf (15,702 N)*

Modulus of Rupture: 21,010 lbf/in2 (144.9 MPa)

Elastic Modulus: 2,115,000 lbf/in2 (14.58 GPa)

Crushing Strength: 10,560 lbf/in2 (72.8 MPa)

Shrinkage: Radial: 3.8%, Tangential: 6.0%,

Volumetric: 10.3%, T/R Ratio: 1.6

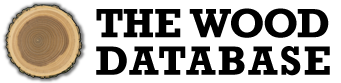

Color/Appearance: Heartwood color typically a light to medium reddish brown, sometimes with darker blackish streaks. Color darkens upon prolonged exposure to light. Pale yellow sapwood distinct from heartwood, though transition is gradual. Can have moderate ribbon figure on quartersawn surfaces due to interlocked/roey grain. Overall appearance can resemble genuine mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla).

Grain/Texture: Quebracho has a fine, uniform texture with a high natural luster. Grain tends to be irregular, roey, and interlocked.

Rot Resistance: Quebracho is rated as very durable, and is also resistant to insect attacks. Quebracho also has good weathering characteristics.

Workability: Difficult to work on account of its density and irregular grain. High cutting resistance, as well as pronounced blunting effect on cutters. Dries slowly—and tends to crack, check, and warp while drying. Turns and finishes well, and also able to take on a high natural polish without any finishing agents.

Odor: There is no characteristic odor associated with this wood species, though it is reported to have a bitter taste.

Allergies/Toxicity: Although severe reactions are quite uncommon, quebracho has been reported as a sensitizer. Usually most common reactions include skin and respiratory irritation, as well as nausea. See the articles Wood Allergies and Toxicity and Wood Dust Safety for more information.

Pricing/Availability: Very seldom available in North America, quebracho is much more commonly harvested and processed for its natural tanins, or minimally-processed and used locally in heavy construction. Small log sections, craft blanks, or sawn lumber can sometimes be found on a limited basis. Expect prices to be in the medium to high range for an imported hardwood.

Sustainability: Quebracho is not listed in the CITES Appendices, and the IUCN reports that Schinopsis lorentzii (listed as S. quebracho-colorado) is a species of least concern, though the synonym S. haenkeana is on the Red List as vulnerable due to a population reduction of over 20% in the past three generations, caused by a decline in its natural range, and exploitation. However, both of these IUCN evaluations date back to 1998 and are in need of updating.

Common Uses: Due its difficult workability, quebracho tends to be minimally processed. Local uses include heavy construction timbers, railroad cross-ties, and fence posts. When exported, uses include furniture, carvings, and turned objects.

Comments: The name quebracho is from the Spanish quebrar hacha, which literally means ‘axe breaker.’ Aptly named, wood in the Schinopsis genus is among the heaviest and hardest in the world. The added descriptor colorado, Spanish for ‘red,’ is sometimes added to the name to help distinguish it from an unrelated species, Aspidosperma quebracho-blanco, which goes by the common name quebracho blanco (white quebracho).

Quebracho was heavily exploited in the late 1800s for use in leather tanning. The tanin-rich heartwood (up to 20-30%) is cut into small chips, where the tanins can subsequently be extracted.[1]Record and Hess. Timbers of the New World. p. 48

In addition to Schinopsis lorentzii (represented on this page), there is another very similar species that is also sold and harvested as red quebracho: S. balansae. According to Record and Hess, Schinopsis lorentzii is “more abundant in the drier western plains and is sometimes referred to as the Santiago type (quebracho colorado santiagueno),” while the closely related S. balansae, also harvested and sold as quebracho, “extends into the swampy lands fringing the Parana and Paraguay rivers, is known as the Santa Fe or Chaco type (quebracho colorado chaqueno).”[2]Record and Hess. Timbers of the New World. p. 48

Special comment on quebracho Janka hardness: This wood previously had a very high Janka hardness value listed, formerly 4,570 lbf (20,340 N), and for several years it also topped the list of hardest woods on the Wood Database. However, a recent discovery of an additional source[3]Martinuzzi, F. (2010.) Fichas Técnicas de Maderas. INTI Madera y muebles. has forced me to recalculate this value. By default, I calculate each of the mechanical values as an average value drawing from all credible/original sources. But for this particular data source, I had ignored the reported values for many years because (i) the authors didn’t list the units of measurement used for Janka hardness, (ii) the values cited did not closely match any known units of measurement for Janka hardness, and (iii) the authors did not respond to my email inquiry. The recent breakthrough finally came when I compared the Janka hardness values of other tree species from this source with their known values from other sources. I could then see that the values corresponded perfectly to decanewtons (daN)—this is a very uncommon unit (Newtons (N) or kilonewtons (kN) are much more common), and it’s the only instance I’m aware of where decanewtons have been used for Janka hardness. However, taken as a whole, the actual data from this source tends to be quite reliable, including the Janka hardness of many other species, so I thought it fit to incorporate the Janka hardness values for this source into the average calculation. This had the effect of bringing the average value down significantly—both for Schinopsis balansae and S. lorentzii.

Images: Drag the slider up/down to toggle between raw and finished wood.

A special thanks to John Volcko for providing the turned photo of this wood species.

Identification: See the article on Hardwood Anatomy for definitions of endgrain features.

Porosity: diffuse porous; growth rings generally not visible, though occasionally discernible due to subtle change in color of woof fibers around the annual growth ring boundaries

Arrangement: solitary and radial multiples

Vessels: medium to large, few to moderately numerous; tyloses common

Parenchyma: vasicentric and unilateral

Rays: narrow width, normal spacing; rays generally not visible without magnification

Lookalikes/Substitutes: Superficially, quebracho has an overall appearance that’s similar to various types of mahogany. However, quebracho’s very high density should serve to separate it from nearly all lookalikes.

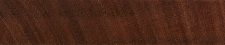

Notes: Heartwood fluoresces a yellowish green under a blacklight.

Related Content:

Another example of quebracho are these luthier bolts. Bolts are quebracho and nuts are ñandubay.

Hello, here you can see a hand threaded quebracho salt shaker. It is a wood I work oftenalong with other extremely hard hardwoods. regards from Uruguay.

The name Quebracho is from the portuguese, not the spanish, since the tree is from Brazil.

No my friend

is from Argentina

Quebracho from the spanish words

Quiebra Hacha

“Schinopsis brasiliensis”

Incredibly tough and heavy wood. immune to rotting. Was heavily used as railway sleepers that lasted 90+ years outdoors..

Newly cut has a bright reddish color, Indoors ages into a dark plum color.

Finishes into a durable natural luster.

Very difficult to machine sawing and almost impossible to drive screws into it unles you make big pilot holes.

Have you heard of quebracho lorentzii? From the Quebracho forest in Argentina.

I am from Uruguay and bought a house some months ago, it was covered all by lower ceilings. I took them out and discovered my ceiling/roof made out of this wood, holding brick. This building style is called “a la porteña” here, and “alla toscana” in Italy.

Anyway, this wood has been resting in these roofs for 140 years, and they still hold the whole roof. It’s majestic, not that hard to cut in my experience, but very very heavy. Sometimes I can’t believe it’s wood, it seems more like some kind of rock.

Is that a freshly cut surface? It looks completely black to me.

Yes it’s fresh. The black part is where I used the angle grinder (which I learned is a big mistake to use that tool). The red part in the center is where I cracked it by standing on it, so really the colour is the one you can see in the stripe in the middle.

Sorry, I can’t tell much from the pictures. I would need to see a finely sanded picture of the endgrain to have a better shot at ID.

I have been spending all day researching hard woods for a base wood to use for personal chopsticks. After being tempted with the idea of buying a set, and I prefer no metal in my mouth, and real real chopsticks go from 130-380 dollars here in US because were idiots, I decided to make my own. Seems to me this wood only causes problems when inhaled dust wise, but I figured if anyone would throw in on taste and tannin results.

Considering the high concentrations of tannins, which can be irritating to skin if remember correctly, and the fact that it’s a pain in the ass to work with. I’d pass, unless you’re dead set about using it in particular. I have a few blanks I was thinking of turning into a pair of nunchucks lol.

I’d use a wood such as cherry, maple, most fruit woods, maybe rosewood if you’re not allergic like I am. Olive wood is a good hard hardwood for utensils I believe. Generally stay away from wood with open pores, high tannins, or toxins/allergens.

Did you make the nunchucks?

Is it possible for me to make a walking/fighting cane out of this wood? Would I be successful? What kinds of tools would I need to work with this? Where can I get some?

If you can find a long section and have the patience. The weight and tendency to splinter isn’t best for a fighting cane though. Try looking at the section for Bow woods on this website(under “Articles”), woods with a decent hardness and a good ratio of modulus of rupture to elastic modulus. Bow woods like Osage orange and yew would make an awesome fighting cane! Janka hardness is not a big deal for fighting canes, Traditional fighting staffs use relatively soft woods

I read that Quercus Myrsinifolia aka Japanese white oak is just perfect for staff type weapons, only problem is I can’t find the Janka hardness for it anywhere on the internet but I found out it’s density is around 54-60 lbs/ft3 from different sources But I can’t tell which one is the most reliable. One last thing the best source I found for how dense Japanese white oak is, is from a company who makes drumsticks called Promark and they say that their Japanese white oak drum sticks are 10% heavier then their hickory drumsticks But they don’t say what… Read more »

I would think Bois d’arc, or Osage Orange, would be relatively easy to find. I have some in my stores here in Alabama. It is aptly named as it was (and is) used for making hunting bows. The heartwood starts out yellow and ages to a really nice medium grey. It’s really tough, and doesn’t splinter.

You’re right, osage is the way to go.

It sounds like seasoning is a major problem. Once the initial drying is over, how is the dimensional stability?

It’s a pity that the wood researchers mostly publish one shrinkage number for initial drying rather than also measuring movement in service.

I’m looking to challenge myself by making a luxury folding wooden rule. Movement in service is clearly an issue, so I was looking at desert ironwood, African blackwood, and other very hard woods. It’s hard to know which is best.

I made a guitar out of this wood (not recommended for people with back problems, it weights more than 7kg and you need a special strap, since the weight will break even a bass strap). This wood does have distinctive odour. The issue is its so hard that if you machine it, you will feel that odour mixed with the burning smell…..is not bitter, but more like a sweet-sour one and it’s very pleasent. The wood is also used in the wine industry (not for barrels but to use the tanines). It is better to work by hand than with… Read more »

Hi Nicolas,

How does this guitar’s neck fare in regards to stability? Was there a need to adjust it often depending on the climate and if so, what kind of climate is it subject to? Is it just as stable as other common guitar necks (mahogany, maple) or better? TIA

Quebracho it’s for Quiebra Hacha, literally Axe Breaker.

I have an axe I keep breaking handles on would quebracho hold up as a handle

I made this video using Quebracho Colorado, enjoy :)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3_bAHQ7ev9E

Cut up a random pallet where I am in the uk made from some tropical wood, didn’t know where it came from but was wondering why it was so heavy. I sanded it and it turns out they used this wood to make this pallet! Interestingly the small amount of sapwood had some rot but the heartwood was perfectly intact after being outdoors for who knows how long. I had to run it through the sander thicknesser as it has interlocked grain that would tear out with a planer. From tapping it, it sounds like it’ll be a great tonewood.

Somebody know the calorific power of quebracho? thanks

Janka hardness says to be 23340N on this page, But if you click on “Top ten hardest woods”, it says 20340N. Wich is correct?

Hmm, looks like a typo. Got it fixed, thanks. The correct value is 20,340 N.

Just curious, would this be suitable for an inlay for a ring?

The cracking effect seems to happen primarily when exposed to the elements. The cracking originates on the outer exposed surfaces progressing over long periods into the inner structure. Common woodworking tools, drills, radial saws will work OK but must be used very slowly. Nails will not work at all because the hardness will only allow a nail to be driven 1/4 inch maximum. Pilot holes for screws again must be made almost at the screws diameter as the wood won’t deflect allowing the screw into the wood.

My grandfather carved a head into a log of quebracho while traveling on a tramp steamer in the ’50s.

The sculpture spent at least 15 years outdoors in new england with little ill effect, and was only brought indoors and treated better after ants moved in. I don’t know that they were feeding on the wood: it does not seem to have been significantly damaged by the ants.