by Eric Meier

Pine is pine, right? Not quite. There’s quite a range in density and strength when it comes to the Pinus genus. Take one of the species of southern yellow pine, Shortleaf Pine, for instance: it has strength properties that are roughly equivalent to Red Oak (with the notable exception of hardness)—and in some categories, such as compression strength parallel to the grain, the pine is actually stronger!

Yet there are also a lot of types of pine that are considerably weaker, and while they certainly have a prominent place in the construction industry, by using all species interchangeably with the generic name “pine,” we create a very inaccurate picture of this interesting wood genus!

It can help to know what you’ve really got, so let’s go over some of the key types of pine seen today:

The Soft Pines

This group is characterized by pines with a low density, even grain, and a gradual earlywood to latewood transition. Species within this group can’t be reliably separated from one another, but it can be helpful to recognize their features in order to distinguish them from the hard pines.There are three principal species of soft pine:

- Sugar Pine (Pinus lambertiana)

- Western White Pine (Pinus monticola)

- Eastern White Pine (Pinus strobus)

Of the three, Eastern White Pine tends to have the finest texture (i.e., smallest diameter tracheids) and the smallest resin canals. Sugar Pine, by contrast, has the coarsest texture and the largest resin canals. Western White Pine falls somewhere between the two previously mentioned species. All species weigh close to the same amount, with average dried weights ranging from 25 to 28 lbs/ft3.

The fourth species in the soft pine group, not nearly as commonly used:

The Hard Pines

This group is somewhat opposite of the soft pines, not only in obvious areas of hardness and density, but also in regards to earlywood to latewood transition, and grain evenness. Hard pines in general tend to have a more abrupt transition from earlywood to latewood, and have an uneven grain appearance (though there can be certain species that are exceptions). Overall, average dried weights for hard pine species range from 28 to 42 lbs/ft3.

Subgroup A: Southern Yellow Pines

The major species in this group fit into the signature hard pine profile: they have the highest densities (between 36 to 42 lbs/ft3 average dried weight), very abrupt earlywood to latewood transitions, and are very uneven grained. All of the species in this grouping are essentially indistinguishable from one another—even under microscopic examination.The four major species of southern yellow pine are:

- Shortleaf Pine (Pinus echinata)

- Slash Pine (Pinus elliotti)

- Longleaf Pine (Pinus palustris)

- Loblolly Pine (Pinus taeda)

Additionally, there are a number of other minor species that comprise southern yellow pine. These species are used much less frequently for lumber than the major species, and have slightly lower densities as well (from 32 to 36 lbs/ft3 on average). Some of the minor species of southern yellow pine are:

- Sand Pine (Pinus clausa)

- Spruce Pine (Pinus glabra)

- Table Mountain Pine (Pinus pungens)

- Pitch Pine (Pinus rigida)

- Virginia Pine (Pinus virginiana)

- Pond Pine (Pinus serotina)

Finally, one additional species is commonly grown on plantations and is nearly identical to the four principal species of southern yellow pine listed above:

Subgroup B: Western Yellow Pines

This grouping can be thought of as an intermediate position between the soft pines and the hard pines. Unlike southern yellow pines, this group doesn’t quite fit the bill of the usual characteristics of hard pines. Although the included species have relatively abrupt earlywood to latewood transitions, they tend to be lighter in weight, (average dried weights range from 28 to 29 lbs/ft3), and have a more even grain appearance. The two main species in this grouping are so similar in working characteristics that they are sold and marketed interchangeably. Construction lumber from this group is stamped with the initials PP-LP, representing the two species of western yellow pine:

Although these two woods are difficult to distinguish from an anatomical standpoint, (Ponderosa Pine tends to have slightly larger resin canals), they can sometimes be separated by viewing the wood on a larger scale.

Ponderosa Pine trees typically have larger trunk diameters than Lodgepole Pine (two to four feet for Ponderosa versus one to two feet for Lodgepole). Accordingly, the wood of Ponderosa Pine usually furnishes wider, more knot-free wood, and has broader arcs in the growth rings when compared to Lodgepole Pine.

A third, much less common species is very closely related to Ponderosa Pine:

Jeffrey Pine and Ponderosa Pine are anatomically indistinguishable, and no commercial distinction is made between the lumber of the two species—both are simply sold as Ponderosa Pine.

A few other miscellaneous yellow pines that are not quite “western,” but share many of the same traits as the species mentioned above are:

Jack Pine grows further east (and north), and is commonly mixed with various species of spruce, pine, and fir and stamped with the abbreviation SPF. Generally, dimpling on flatsawn surfaces will appear more subdued and less common in Jack Pine than in Lodgepole Pine.

Native to coastal California, today Radiata Pine is grown almost exclusively on plantations—most notably in Chile, Australia, and New Zealand. In the southern hemisphere, where true pines are essentially absent, it’s the most commonly cultivated pine, and is valued for its fast growth and utility—both as a source of construction lumber, as well as wood pulp in the paper industry.

Subgroup C: Red Pines

In the United States, this group is composed of only one species:

There’s also a couple of closely related species found in Europe:

Subgroup D: Pinyon Pines

Earlywood to latewood transition abrupt, narrow growth rings, numerous resin canals, increased weight, small diameter, interesting smell, seldom used for lumber.

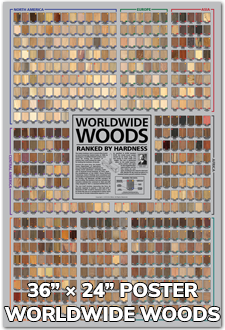

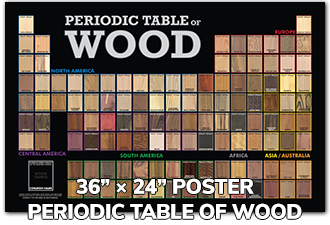

Get the hard copy

Would any of the soft pines make a good acoustic guitar soundboard?

Eastern White or Sugar Pine would be your best bet. They’re the lightest of the pines. Eastern White is a little stiffer than Sugar (which is good for a soundboard). Using averages for the species, you’d want to make either species 3.1 mm thick (using the Trevor Gore thicknessing formula). Should be similar to Sitka (2.9 mm).

As with any species used for an acoustic top, you want vertical grain and completely clear.

It will sound good, but if you want great, try Lutz, Engelmann Spruce, or Western Red Cedar. The lighter, the better.

I have had Canary Island Pine used for Cabinets and flooring in my house. I had it sawmilled onsite when an 80 year old tree was being taken down due to bark beetle killing it in 2015. This is was in Eagle Rock (Los Angeles, CA). I had to take it to a mill in Santa Clarita for planning because the local milling places considered it “too sappy” for their equipment. It is so beautiful with the dark heartwood and lighter areas. I used no stain. I have searched for the Janka hardness on it and cannot find it for… Read more »

Hello, do you have any information on Japanese/asian variants of pine wood? Like the Japanese cypress pine?

No, not yet. But Japanese cypress pine is actually Chamaecyparis obtusa, which isn’t really a pine wood at all, and would be much closer to what we would consider a cedar or cypress here in North America. Here’s a closely related species: https://www.wood-database.com/port-orford-cedar/

What about Oregon pine?

Oregon pine = Douglas fir, so not actually a true pine. https://www.wood-database.com/douglas-fir/

Thank you, that’s helpful to know.

Can I use natural pine for furniture? It’s not dressed. Pine just says on the piece natural pine and does it need to age?