by Eric Meier

In the Eastern United States, and perhaps spilling over into adjacent geographic regions, there are a group of hardwoods that have similar appearance, mechanical properties, and anatomy. For lack of a better name, I’ll simply call them the golden heavy hitters.

Here’s the lineup:

Briefly, these woods all have a few things in common.

- They are ring-porous hardwoods, native to North America.

- They all have heartwood that ranges from light yellow (when freshly sawn) to golden brown, eventually darkening to a darker russet brown.

- They are among the heaviest domestic hardwoods, with dried weights ranging from about 42 lbs/ft3 to 54 lbs/ft3 (675 kg/m3 to 855 kg/m3.)

Color alone is not a reliable means of identification

The first thing to note, which is good advice for separating many different wood species far beyond the scope of this article, is that color is not a reliable means of identification. This is especially true of the woods in this category, because they tend to shift color over time. Most of these woods begin a pale yellowish color, and age to a darker russet brown.

Of course, there are subtle differences in the color of each species, so it ought not be completely discounted, but in reality, color alone should never be the determining factor in separating these woods.

Two diagnostic checks make everything easier

With these woods, there are two checks that you can perform to immediately narrow down the field. Unfortunately, they aren’t as easy as the prevailing ‘wisdom’ of just looking at the facegrain and making a wild guess. You may have to do a little bit of work in preparing the wood surface, and/or picking up some supplies. (If wood ID were as easy as a quick glance, there’d be no need for wood anatomists.)

1. Check for tyloses

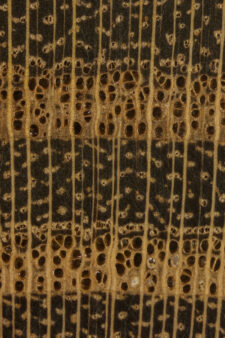

Much like the method used for distinguishing between red and white oak, the first test requires a clear, magnified view of the endgrain.

What you are looking for are the little bubble-like structures filling all the pores along the growth ring. Notice above that the black locust has pores that are packed with tyloses, while the mulberry sample, while otherwise very similar to the locust, lacks these tyloses.

Pro tip: do not confuse sanding dust for tyloses. After working with any wood, the endgrain pores will almost inevitably be filled with whitish sanding dust. Make sure to take some compressed air and blow out all the dust first—the tyloses, like the three little pigs making a house of brick, will remain and can’t be blown out.

2. Check for fluorescence

Readers may be surprised to discover that some of these golden woods will glow (the scientific term for this is ‘fluoresce’) when exposed to a blacklight. Indeed, these woods produce some of the strongest fluorescent responses of all known woods worldwide, glowing a vibrant yellow-green.

The test for fluorescence is fairly straightforward, and involves using a blacklight bulb available at most big box hardware stores and home centers. Simply shine the light on a fresh wood surface in a completely darkened room and check for fluorescence. You can read about the process a little more in my article specifically detailing wood fluorescence.

Putting it all together

With the two checks performed, we can start to put the pieces together and get a clearer picture on wood ID.

| Tyloses | Fluorescence | |

| Black locust | ||

| Honey locust | ||

| Kentucky coffeetree | ||

| Osage orange | ||

| Red mulberry | VARIABLE |

Final sorting

Referencing the diagnostic chart above, we’ll consider each grouping separately.

1. Black locust

In a group of its own, though it a blacklight is not available, it can be confused with osage orange (and to a lesser extent, mulberry).

2. Honey locust and Kentucky Coffeetree

Of all the woods on this list, these two are probably the trickiest to separate. As a matter of face, I’ve even personally ordered a piece of Kentucky coffeetree and received a misidentified piece of honey locust instead.

The trick is in the latewood pore arrangement. In honey locust, the latewood pores tend occur in more of a diagonal or wavy pattern, while Kentucky coffeetree’s latewood pores will occur in clusters. This clustering is so distinct that coffeetree is very commonly used as the textbook example of pore clusters.

3. Osage orange and red mulberry

One attribute about osage orange that makes it easy to separate from other lookalikes is that its heartwood extractives are readily leachible in water—and will discolor the water a yellowish color.

4. Miscellaneous honorable mentions

In addition to the woods listed on this page, there are a handful of other ring-porous hardwoods that also occur in the eastern United States (as well as Canada and the Midwest, etc.) which can sometimes be confused with these golden woods, but usually have an easy giveaway clue that makes them readily distinguishable from the others.

Catalpa is a ring porous wood with a similar appearance and anatomy, but it is very lightweight and soft—almost half the weight of some of the other woods listed here!

Ash can have a similar superficial appearance and anatomy. But it generally lacks the yellowish gold color of the other woods (as well as lacking both tyloses and fluorescence).

Just wondering… I once cut down a very old and large black locust. The very oldest part, where the girth was greatest, had an extra core of heart wood that was black. There was sapwood, brown heart wood, and in the very center, a black core. Has anyone else ever seen this? I took some home to feed my wood stove, and found it to be the best fuel I’d ever seen. It burned like coal. Very low, blue flames, and it lasted much longer than anything else. Only saw the one example though.

Trees growing around steel fence posts and sometimes with iron embedded in them (nails or spikes) can become stained black from the metal. Sometimes they will pul up iron fromnthe dirt into the core wood and become stained that way. Iron stained wood will often times produce blue flame when burned.